Ozempic and other GLP-1 drugs are reshaping food, beauty, alcohol, and belonging. From snack sales to body ideals, marketers are rebranding around the “Ozempic Nation.”

The Smell of Shame

How sex sells shame

Sex has always been the magic wand of advertising, but it’s not just about getting the sparks flying. When it comes to selling all-over body deodorants, it’s less about the promise of passion and more about the dread of rejection. These ads know exactly where to poke—the tender spot of our insecurities—promising not just attraction, but salvation from embarrassment, awkward encounters, and the dreaded social exile. They skillfully dangle the dream of desirability in front of us, suggesting that with their product, you won’t just smell better—you’ll be better, period.

From the earliest days of commercial deodorants, marketing played on the notion that one’s natural body odor could be a make-or-break factor in attracting a partner. An underlying message persists: if you don’t smell pleasant, your chances of intimacy, sex, and love are threatened. The equation is simple—bad odor equals bad sex life, no odor means desirability. This messaging leverages shame to compel action, pushing the consumer to purchase a deodorant that guarantees “freshness” and “confidence.”

The rise of shame-based deodorant advertising

All-over body deodorants first hit the scene in the early 20th century, back when personal hygiene was the new kid on the block. At first, they were peddled like little miracle cures for medical woes like excessive sweating—hyperhidrosis if you’re feeling fancy. But as time went on, deodorants got a makeover. No longer just a doctor’s recommendation, they became a daily “must-have,” with the messaging shifting from “fix your sweat” to “fix your social life.” Suddenly, smelling good wasn’t just healthy—it was mandatory for social survival.

One of the earliest examples of this trend is Odorono, one of the first commercially successful deodorants. Launched in the early 1900s, Odorono employed what is now considered a textbook case of shame marketing. In the 1910s, a famous Odorono ad proclaimed, “Within the Curve of a Woman’s Arm. A frank discussion of a subject too often avoided.” The ad did not just suggest that body odor was undesirable—it implied that it could directly impact a woman’s social and romantic success. This tactic sparked a powerful psychological reaction, making people question their natural smells and linking body odor to personal failure and shame.

The Who’s parody of Odorono in their song humorously critiques the absurdity of deodorant ads by telling the story of a singer whose promising career falls apart—all because of a missed opportunity blamed on body odor, poking fun at the exaggerated stakes these advertisements create.

Vintage ads and shame-based strategies

Vintage deodorant ads offer a revealing glimpse into the evolution of shame-based marketing tactics. These advertisements didn’t just sell a product—they sold an ideal, where cleanliness and odorlessness were equated with social acceptance, attractiveness, and worthiness. Let’s take a look at a few examples and dissect the shame-inducing messages behind them.

Lifebuoy’s “B.O.” Campaign (1920s-1930s): Lifebuoy introduced the concept of “B.O.” (body odor), a term that rapidly gained cultural traction. By naming and framing body odor as an identifiable, shameful issue, Lifebuoy created a problem that their product could solve. Their ads played on the fear of being socially rejected due to bad smells, featuring anxious individuals surrounded by judgmental glares and whispers. The messaging was potent—if you don’t take care of your body odor, you’ll become an object of ridicule.

Lysol’s Feminine Hygiene Ads (1930s-1960s): Although not a deodorant product, Lysol’s ads for feminine hygiene exemplify how shame marketing extends beyond underarm odor to encompass all-over body deodorants. Although not a deodorant product, Lysol’s ads for feminine hygiene exemplify how shame marketing extends beyond underarm odor to encompass all-over body deodorants. Marketed as a “feminine hygiene” product to prevent “intimate neglect,” the ads discreetly hinted at douching for odor control while also serving as a veiled solution for contraception, at a time when discussing birth control openly was taboo. These ads tapped into both the fear of being unattractive to a partner due to body odor and the societal pressure to discreetly manage one’s fertility, making Lysol a household product with an unspoken, dual purpose.

Mum’s “Keeps You Nice to Be Near” Campaign (1950s): In the 1950s, as rigid gender roles reigned supreme, ads like Mum’s took it upon themselves to teach women a valuable lesson: smelling good wasn’t just about hygiene—it was about securing your romantic future. One particularly blunt ad declared, “That left out feeling can crush a flower girl,” suggesting that even the most beautiful woman might be left without a date if she’s guilty of the “fault men don’t overlook.” The message? If you don’t want to be the one standing solo at the dance, you better guard against underarm odor. According to Mum, the secret to being “nice to be near” was a good swipe of deodorant to guarantee your charm didn’t go to waste.

Mum’s “Keeps You Nice to Be Near” Campaign (1950s): In the 1950s, as rigid gender roles reigned supreme, ads like Mum’s took it upon themselves to teach women a valuable lesson: smelling good wasn’t just about hygiene—it was about securing your romantic future. One particularly blunt ad declared, “That left out feeling can crush a flower girl,” suggesting that even the most beautiful woman might be left without a date if she’s guilty of the “fault men don’t overlook.” The message? If you don’t want to be the one standing solo at the dance, you better guard against underarm odor. According to Mum, the secret to being “nice to be near” was a good swipe of deodorant to guarantee your charm didn’t go to waste.

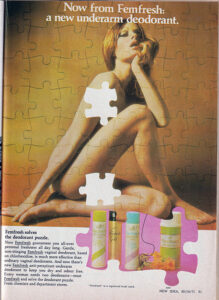

Femfresh “A new underarm deodorant” (1970s): In the 1970s, Femfresh entered the scene with a bold claim: it had solved the “deodorant puzzle.” This puzzle, apparently, was that one deodorant wasn’t enough. Femfresh advertised itself as the answer to “all-over personal freshness,” offering both a vaginal deodorant and a separate underarm antiperspirant. The ad’s messaging was clear—women needed two different deodorants to stay odor-free and dry all day long. With phrases like “gentle, non-stinging” and claims of being “much more effective than ordinary vaginal deodorants,” Femfresh sought to carve out a space as an essential product for women’s hygiene. It emphasized that full-body odor control was not just about armpits but all “feminine” areas, implying that only by using Femfresh could a woman achieve true cleanliness and confidence from head to toe. The brand leaned heavily on the idea that maintaining multiple products was key to personal appeal and that regular deodorants just couldn’t keep up.

Femfresh “A new underarm deodorant” (1970s): In the 1970s, Femfresh entered the scene with a bold claim: it had solved the “deodorant puzzle.” This puzzle, apparently, was that one deodorant wasn’t enough. Femfresh advertised itself as the answer to “all-over personal freshness,” offering both a vaginal deodorant and a separate underarm antiperspirant. The ad’s messaging was clear—women needed two different deodorants to stay odor-free and dry all day long. With phrases like “gentle, non-stinging” and claims of being “much more effective than ordinary vaginal deodorants,” Femfresh sought to carve out a space as an essential product for women’s hygiene. It emphasized that full-body odor control was not just about armpits but all “feminine” areas, implying that only by using Femfresh could a woman achieve true cleanliness and confidence from head to toe. The brand leaned heavily on the idea that maintaining multiple products was key to personal appeal and that regular deodorants just couldn’t keep up.

The shame-and-spray trap

These ads have one thing in common: they create the “problem” and conveniently offer the “solution.” It’s not just a bottle of deodorant—they’re selling a lifestyle of dependency. The genius of shame-based marketing is planting a seed of insecurity and letting it grow until you believe that your natural self is inherently flawed. Suddenly, deodorant isn’t a choice—it’s a must-have, an “essential” fix for your so-called embarrassing problem.

In psychological terms, it’s like turning up the volume on our natural fear of being left out. Once they make you feel like your body odor is the fastest ticket to social exile, you’ve got two options: grab that deodorant to win back your “acceptability,” or risk being the smelly pariah no one wants to be around.

Take Lume, the modern all-over body deodorant that markets itself as the savior of “down there” odors. Their ads love to show people squirming over intimate-area scents before offering Lume as the anxiety antidote. The language may have shifted to embrace body positivity, but let’s not kid ourselves—the message hasn’t changed: your body smells bad, and only Lume can save you.

Modern marketing and the softer shame game

Vintage ads hit you over the head with shame. Nowadays, brands have swapped the hammer for a velvet glove. “Confidence,” “freshness,” and “comfort” are the new buzzwords—but scratch the surface, and you’ll find the same implication: to be liked, loved, and confident, you need to be odor-free. The shame is there; it’s just wearing a nicer outfit.

This subtlety works perfectly with the self-care and wellness movements, sliding all-over body deodorants into your routine as part of “feeling good.” Sure, they focus on the benefits, not the “problem,” but the emotional hook is still hanging on the same peg—fear of embarrassment and pressure to conform to society’s unwritten “rules” of cleanliness.

Gender dynamics: Pink for shame, blue for swagger

A peek into deodorant ads shows different shame-playbooks for men and women. Women have always been the main target for all-over body deodorants, with ads promising attractiveness, popularity, and the happily-ever-after all hinging on staying odor-free. For men, it’s a different ballgame—deodorant is about enhancing strength, performance, and, of course, sexual appeal. Smell great, assert your dominance, and conquer the world.

Interestingly, for men, the pitch isn’t about avoiding shame—it’s about amping up your appeal. Brands like Old Spice and Axe don’t tell guys they “stink” in an embarrassing way; they tell them they could smell better to attract more attention, make a bolder impression, and be more “manly.” The goalposts are different, but both strategies drive you toward the same place—the checkout counter.

Fresh scent, stale planet: The environmental angle gets complicated

While shame-based marketing is nothing new, there’s a growing complication for deodorant brands: an eco-conscious generation that’s not so easily guilt-tripped into consumption. For decades, convincing us that deodorant is an everyday must-have has meant endless purchasing, but the new wave of consumers is paying closer attention to the waste that comes with it. Every swipe, spray, and roll-on isn’t just leaving you odor-free—it’s leaving a trail of plastic packaging, chemical ingredients like aluminum, and artificial fragrances that pile up in landfills and oceans.

When sustainability matters just as much as smelling good, it’s not enough to just say, “Don’t stink,” anymore—they’ve got to make us believe that a fresh scent is somehow more important than a fresh planet. And the challenge? Shaming a generation that’s as suspicious of excess consumption as they are of bad B.O. is going to take a lot more finesse.

@krystalynngier Is Native sustainable or is it greenwashing? Two years ago I said it was greenwashing, so let’s see if anything has changed… Welcome to “sustainable or greenwashing month” where I see if brands and products are actually what they say they are. 🕵️♀️ Native was founded as a way to to make “clean” & “nontoxic” deodorant which has since moved into other body care products. As we know, words like “clean” and “nontoxic” aren’t regulated – so let’s dive into what that means for Native. Ingredients are Phthalates free, Paraben free, cruelty free (without a third party certification, so to me that doesn’t really count), and their scents abide by the International Fragrance Regulatory Association (IFRA). *deodorants are aluminum & talc free. All products are made in the USA, but they are owned by P&G & their formulas are not considered biodegradable. The cool thing about Native is they offer plastic free deodorant which I love, but they promote the brand to be 1% for the planet, but in reality it’s ONLY for the plastic free deodorant (???? thats wild to me, why is it not every product??) I’m actually going to include a screenshot of the only environmental statement on their website here and to be honest, this is just screams greenwashing: “Plastic doesn’t make perfect, and we’re doing our part to help. Reducing our environmental impact is nuanced, difficult, and important work—and while we can’t promise to get it right every time, we can promise to be upfront and honest about our efforts. If you’ve ever read one of our ingredient labels you know transparency is sort of our thing.” SO, for a popular brand that would have the money and resources to do better – I’m disappointed because they definitely tout their products to be “natural” and “clean” – and maybe they are better than other brands – but they just don’t cut it for me. I’m gonna say greenwashing – but what do you think? This month we’re doing an ENTIRE month of Sustainable or Greenwashing videos, so if there is a brand you want to see, stick around because it’s probably coming. #sustainableorgreenwashing #native ♬ L.Boccherini, Minuet from String Quartet No.5 in F major – AllMusicGallery

So what’s the play? We’ll likely see brands ramping up “natural” and “sustainable” messaging to convince consumers that their deodorant habit is both a self-care ritual and an act of eco-heroism. But whether that spin will stick with a generation that’s already wising up to greenwashing is a different story. Either way, the classic dance of deodorant shame will need to find new steps to keep consumers feeling fresh—and buying.

Breaking the Stink Cycle

A deep dive into all-over body deodorant marketing reveals a longstanding tradition of selling shame to make us buy. From blunt, vintage ads to today’s “empowering” yet subtly shaming language, the core message remains: your natural body isn’t good enough, and deodorant is the answer to all your social fears.

But here’s the twist—awareness is growing, and with it, a pushback. There’s a rising counter-movement challenging the idea that natural body smells are undesirable. This movement encourages body acceptance, especially among women, urging people to embrace their natural scents. Experts and advocates remind us that the vulva only needs mild soap for cleansing and that the vagina is self-cleaning, with a natural scent that shouldn’t be masked by perfumes or harsh products. This perspective is gaining traction through body-positive campaigns, social media education, and advice from healthcare professionals who seek to dismantle the notion that a body should smell like anything but itself.

Ultimately, it’s about finding a balance—a middle path between extremes. Awareness lets us choose whether we reach for deodorant because we want to, not because an ad dictates that our natural scent needs fixing. And perhaps, as we learn to question these norms, we might all reclaim a little bit of our natural aroma in the process, leaving behind the decades of anxiety stirred up by shame-based marketing.

They’ve got their hooks in you.

FADS rise quickly, burn hot and fall out. They say you’re fat, you’re no fun, you need to relax, and you might even die alone.

In fact, FADS bank on the fact that you already believe all of that.

Ready to learn how it works?